In the far east of Serbia can be found a very special example of ancient Roman culture: a splendid, breathtakingly beautiful palace built under Emperor Galerius Valerius Maximianus within an imposing and architecturally unique fortress.

Emperor Galerius Valerius Maximianus (ruled 293-311) was born in the middle of the 3rd century in the valley of the river Crna Reka, not far from the modern Serbian city of Zaječar, and it was in this valley, protected on all sides, that he erected his residence at the end of the 3rd and beginning of the 4th century, calling it Romuliana after his mother, Romula.

The complex is a special type of monument to Roman court architecture. The palace was built on the instruction of the Emperor as his retirement home and is at the same time the place in which he was buried and deified.

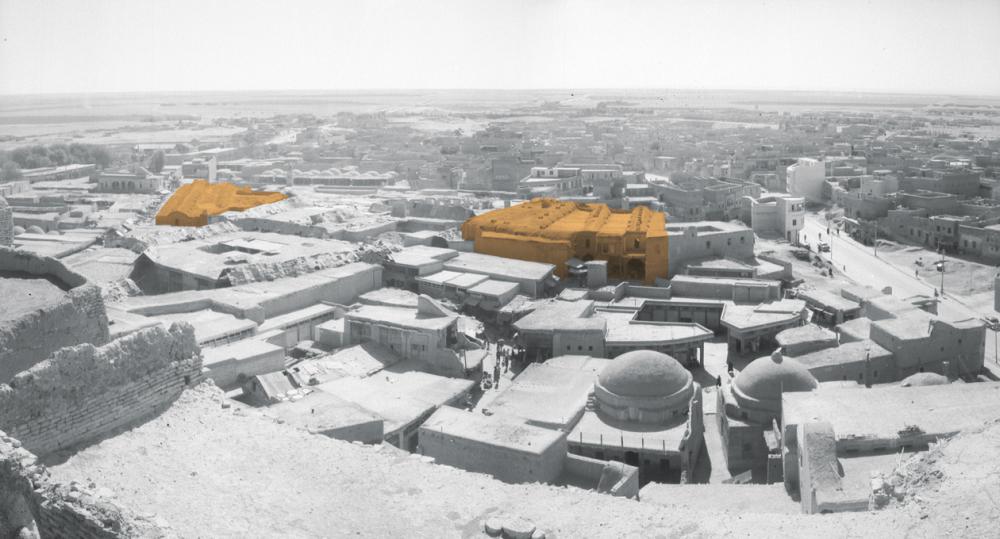

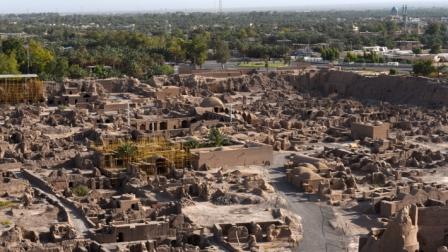

The visible parts of the complex were mentioned by travel writers back in the 19th century. The archaeological excavations which began in 1953 revealed the remains of the older and newer fortified palaces as well as numerous buildings serving public and private purposes.

The two palaces and the other buildings dating from that time were built in a relatively short period of 14 years (from 297 to 311). The single roadway which once linked the east gate (which has been restored and preserved under the Cultural Preservation Programme) with the west gate divides the complex into a north and a south section, each of which was used for different purposes. The northern half was the site of the imperial palace with a small temple and a sacrificial shrine in the courtyard; the southern half held public buildings (a large temple with two crypts and rect angular foundations and thermal baths) and the palace’s ancillary buildings.

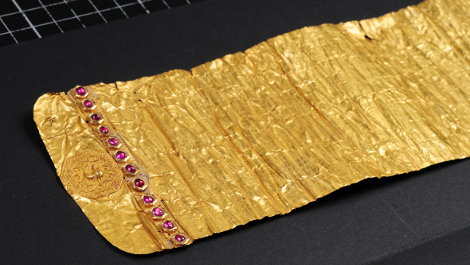

The palace is decorated with wonderful mosaic floors with abstract motifs and figures. The most important of the numerous fragments of sculpture found during the excavations is the head of Emperor Galerius from a monumental porphyry sculpture.

In the light of its architectural value, but also because of the beauty and quality of the artworks, especially the mosaics, and as it is still a working archaeological site, Romuliana was included in the UNESCO World Heritage List in 2007.

Project: Bora Dimitrijević, Project Director, Director of Zaječar National Museum

Promoted by: Cultural Preservation Programme of The Federal Foreign Office

Source: Worlds of Culture, Ed. Federal Foreign Office