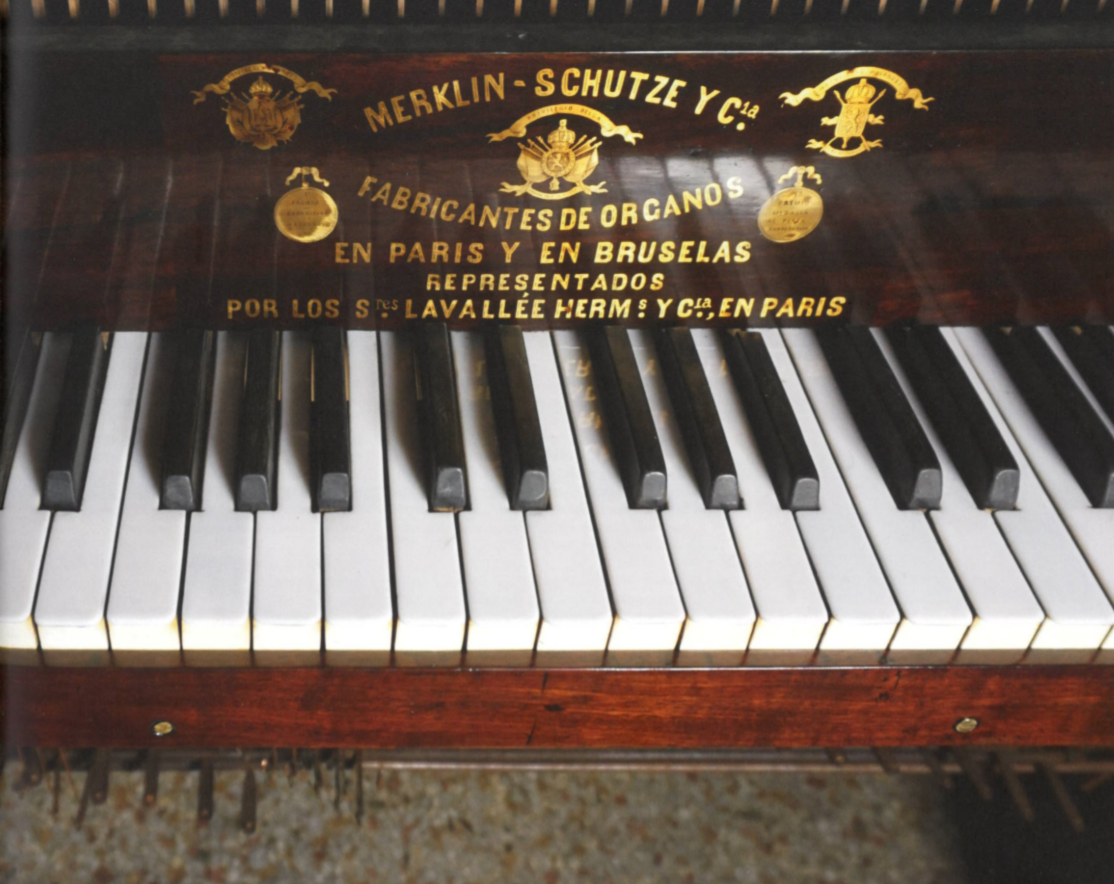

The historic Merklin-Schütze organ in Havana was built in 1856 for the Iglesia de la Caridad in Old Havana, the city centre which is now recognised as UNESCO World Heritage. The instrument is not only among the country’s most valuable organs in terms of craftsmanship and artistry, but is also one of the oldest surviving organs in the entire Caribbean. The restoration project will make it playable again, opening up new possibilities for Cuba’s sacred music culture.

South America

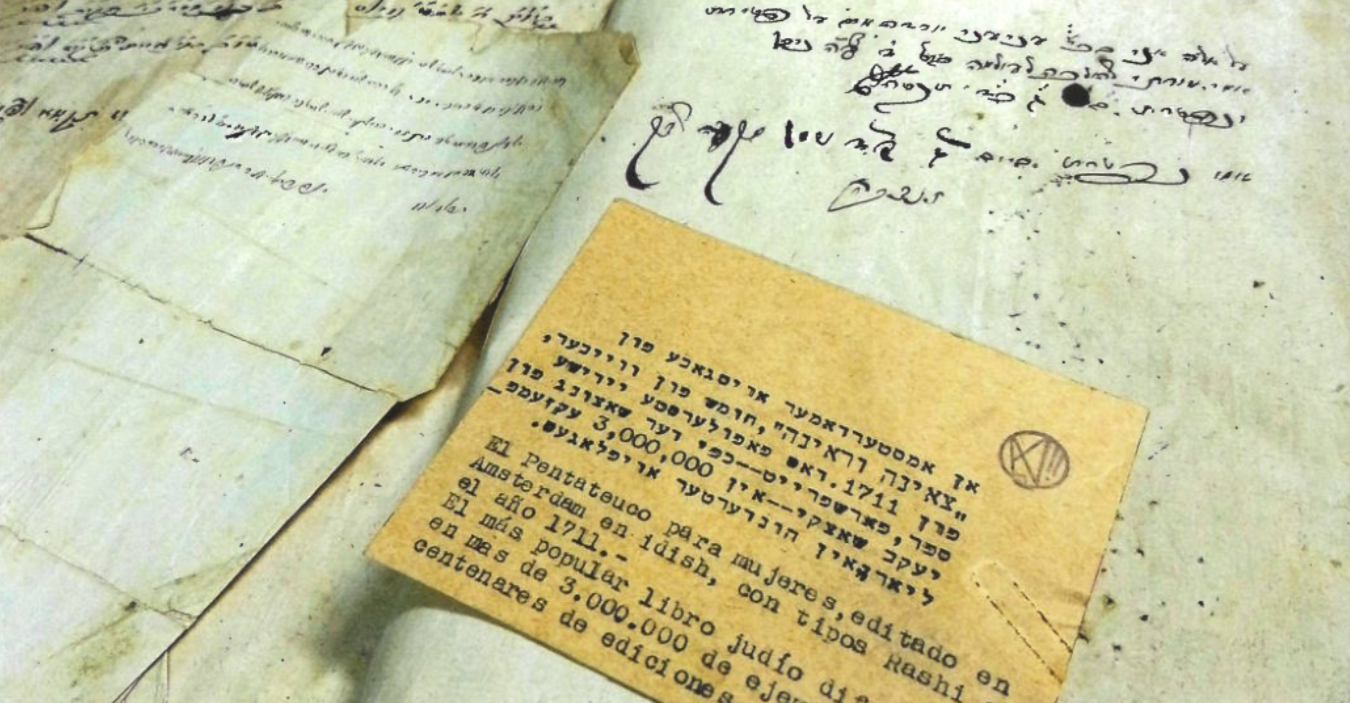

Reconstruction of the Archive Material of the Instituto Judío de Investigaciones, IWO (Argentinia)

On 18 July 1994, the Asociación Mutual Israelita Argentina (AMIA) building in Buenos Aires, the centre of the Jewish community in Argentina, was destroyed in a bombing. The building, which housed numerous Jewish organisations and associations, was completely destroyed. 85 people were killed and 300 injured, and over 400 nearby homes and businesses were destroyed or damaged. To this day, it remains unclear who was responsible for the attack.

Preserving the cultural heritage of the Aché (Paraquay)

With the help of funding from the Cultural Preservation Programme of the Federal Foreign Office, the endangered indigenous cultural heritage of the Aché in Paraguay has been preserved for the future.

With the help of funding from the Cultural Preservation Programme of the Federal Foreign Office, the endangered indigenous cultural heritage of the Aché in Paraguay has been preserved for the future. Preserving the Aché culture is important for future generations, as it is part of Paraguay’s culture. The Aché were persecuted and sold as slaves until the 1970. Only a few older members of the Aché have survived and are able to hand on the old traditions orally.

Their memories will be documented and preserved in the cultural heritage project. Alongside documentary films, a virtual museum with its own exhibits will be set up, with the aim of preserving the indigenous group’s history, which is handed on orally from generation to generation, and traditions. The persecution of the Aché was revealed in Paraguay in 1972 through a text by German ethnologist Mark Münzel, who drew international attention to the tragedy of the Aché. Around 1880 Aché currently live in seven groups. They are a minority among the country’s indigenous population.

Three documentary films of around 45 to 60 minutes record and translate stories by the oldest Aché and document the group’s rituals, handicrafts and music. The virtual museum will also present the history and culture of the Aché. During the project, the Aché made traditional objects for the museum. The virtual museum will be made available to pupils from indigenous groups and the general public. The aim is also to provide online teaching material on the culture of the Aché.

The project is being carried out with the NGO Asociación Madre Tierra, which was founded in 1993 and has focused on work with indigenous groups since 2003. It facilitates direct contact with the community’s chief and head teacher, who in turn inform the members of the community about the films and museum. The aim of the project is to preserve a culture that is at risk of dying out by using modern technology to record the group’s oral history and traditions and making them available to the public.

Promoted by: Cultural Preservation Programme of The Federal Foreign Office

Source: Ed. Federal Foreign Office

The Nasca Elite Burials of La Muña (Peru)

Nasca Elite Burials from La Muña: Restauration and Development for Tourism of an Archaeological Site of the Middle Nasca Culture (AD 200 – 400).

La Muña is one of the most impressive archaeological sites of the Middle Nasca Culture in the province of Palpa on the Southern coast of Peru. The site shows a plurality of archaeological features as elite burials, terrace structures, platforms and geoglyphs. In the years 1998 and 2001 several areas of the site were excavated by the DAI but were filled up again for reasons of conservation. During the years 2012 and 2013 two elite burials were reexcavated, restored and prepared for tourism. An information center was erected to provide information on the archaeological work done and to show its results.

Source: German Archaeological Institute

Restoring and relocating the Merklin-Schütze organ in Havana (Cuba)

The Federal Foreign Office has supported the restoration of the historic Merklin-Schütze organ in the Iglesia San Francisco de Asis in Havana as part of its Cultural Preservation Programme since October 2017.

Built in 1858 for the Iglesia de Caridad in Havana, this almost fully preserved organ, which has been unplayable for decades, is one of the most valuable cultural assets of the historic part of the old town in Cuba’s capital, protected by UNESCO. The Iglesia de la Caridad del Cobre is one of the most important churches in Havana. The instrument is not only among the best organs in the country in terms of craftsmanship and artistry, but is also one of the oldest preserved organs in the entire Caribbean.

Baltisches Orgel Centrum Stralsund e.V. (Baltic organ association, BOC) is completing the restoration of the organ built by the two renowned German masters Joseph Merklin and Friedrich Schütze in cooperation with the local restoration workshop Oficina del Historiador de la Ciudad de La Habana and veteran Swiss organ builder Ferdinand Stemmer. Cuban craftsmen are being trained to maintain the instrument in the future. After undertaking scientific research on comparative instruments, stock-taking and purchasing necessary materials and tools, the complete organ mechanism was entirely dismantled and transported from the Iglesia de Caridad to the Iglesia San Francisco de Asis for restoration in November 2017, where the pipes were also repaired and cleaned. During the further course of the project, the casings will be restored and the ongoing work will continue to be documented.

Music as a bridge between cultures

A playable, fully restored historic church organ in line with good conservation practice is the objective of this comprehensive restoration project. Musical events with soloists from Cuba and abroad can be held that will help to foster both international exchanges of musicians and the tourist industry. Moreover, the historic organ is urgently needed for training church musicians and for supporting church music in general. Thanks to a cooperation agreement between the Instituto de Estudios Eclesiásticos P. Félix Varela and the College of Catholic Church Music and Musical Education in Regensburg, young organists have had the opportunity to receive training in Havana since 2016. This is the first time that Catholic Church Music has been offered as a university subject in Cuba. Students will be able to use the organ during their studies after the restoration work has been completed.

The Iglesia San Francisco de Asis, a restored church in the heart of Havana’s old town protected by UNESCO, is one of the most important tourist attractions and a major venue for classical concerts such as the annual Semana de Música Sacra.

Thanks to the restoration of the Merklin-Schütze organ with funds from the Cultural Preservation Programme, an important testimony to Cuba’s cultural past is being preserved for future generations.

The project partners are the German World Heritage Foundation and the Baltisches Orgel Centrum e.V., as well as the Archbishop’s Office of the Roman Catholic Church in Cuba. The project is being completed in connection with the church music training programme recently launched by the Catholic Church in Cuba.

Promoted by: Cultural Preservation Programme of The Federal Foreign Office

Source: Ed. Federal Foreign Office