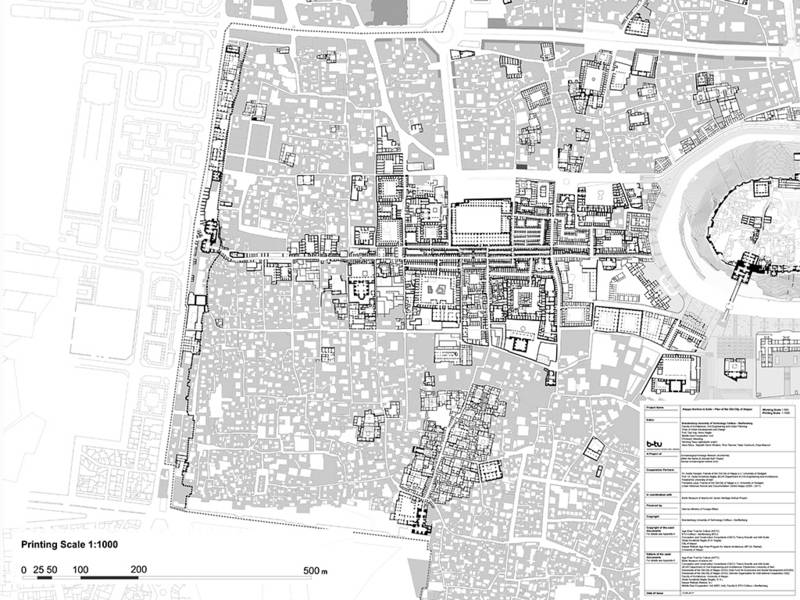

Urban morphological ground-plans of the development of old city Aleppo

The pictures became viral and spread around the world: Once one of the largest trade centres in the Middle East, now a city remained in ruins. Scientific researchers of BTU Cottbus – Senftenberg have worked out on foundational documentations for future planning toward reconstruction of the city, particularly including a detailed digital map of the old city of Aleppo.

Aleppo, second largest city in Syria and one of the oldest continuously inhabited settlements in the World, has been suffering for six years under the civil war. Prior to the clashes 2,5 Million people lived in the city. Today more than half of the population have fled their homes. During the civil war large parts of the city, in particular the old city which was declared as a World Heritage Site by UNESCO since 1986, have been severely damaged.

Under the supervision of the project manager Christoph Wessling, researchers had to deal with a never-ending task. Around 20 Gigabyte data were systematically worked out and further included within the map of the old city on the printing scale of 1:1000 (working scale of 1:500), which illustrates the urban structure and built status by the year 2011.

Until shortly before the outbreak of the civil war, the urban planners and architects of the university were involved in a cautious renovation and revitalization of the old city which was threatened by decay and depletion. In 2004, the German-Syrian project which was supported by the Deutsche Gesellschaft für Technische Zusammenarbeit (German Corporation for Technical Cooperation) with € 20 million of funds, was awarded the Harvard School of Design prize, in the category of urban design and planning. At present the collected data of that time have been instrumental in facilitating the reconstruction process. The map has been created based on the cadastral plans of Aleppo and includes 16000 parcels of the old city, around 400 ground-plans of significant buildings such as the Souq area, the Citadel, the buildings south of the Citadel and numerous buildings, among others in the quarters of Bandarat Al-Islam, in Al-Jidayda as well as in Al-Bayade and Jibqarman.

Numerous maps and planning documents with ground floor plans and the recently designed public spaces have been included in the map. Moreover, the most significant urban transformations of the 20th century could be further traced through overlaying the urban and parcel structures of the 1937 cadastral plans with that of the pre-war cadastral plans. As a result, the urban structure that is currently hidden under the building ruins became visible. Where today only rubble can be seen, the map shows the foundation walls, paths, alleyways and parcel structures underneath.

With downloads!

Source: https://www.b-tu.de/middle-east-cooperation/research/research-projects/aleppo-archive-in-exile