The publication of The Best in Heritage 2020 is online and free to download now. In the category „Project of Influence“ 2020 the project “Stewards of Cultural Heritage” was awarded with the the secon prize.

General category

Stone Conservation at Nanpaya Temple (Myanmar)

On 24 August 2016, an earthquake measuring 6.8 on the Richter scale hit Bagan, one of the world’s most important historical cultural sites. Almost 400 of the around 3000 sacred architectural works were damaged, some of them seriously. The extremely heavy spires of many temples fell to the ground, while centurie sold masonry became loose, cracking precious murals and stucco decorations. Germany was one of the countries which responded to the urgent appeal for international help, sending three experts with many years of experience in cultural preservation in South-East Asia to Bagan to discuss suitable conservation and restoration measures with local officials.

Sudan Digital: A Digital Heritage Registry for the Sudan

The Sudan boasts a rich cultural heritage encompassing important ancient artefacts. The Sudan Digital project, in

collaboration with the National Corporation for Antiquities and Museums (NCAM), aims to ensure the protection of these sites and objects through the creation of a digital heritage registry. The starting-point for this task is the archive of the German architect and building researcher Friedrich W. Hinkel, which contains valuable information on over 14,000 archaeological and historical sites in the Sudan. This archive has been digitised, with funding from the Qatar-Sudan Archaeological Project between 2014 and 2016 and from the Cultural Preservation Programme of the Federal Foreign Office since 2016.

Iraqi-German Expert Forum On Cultural Heritage (Iraq)

Iraq has a very rich archaeological and architectural heritage. Preserving this is the prime goal of the Iraqi-German Expert Forum on Cultural Heritage (IGEF-CH). This forum for dialogue aims to familiarise the staff of Iraq’s State Board of Antiquities and Heritage with modern archaeological methods for documenting and conserving structures and to support them in their work. At the same time, it serves as a platform for scientific and academic exchange on various approaches to cultural preservation.

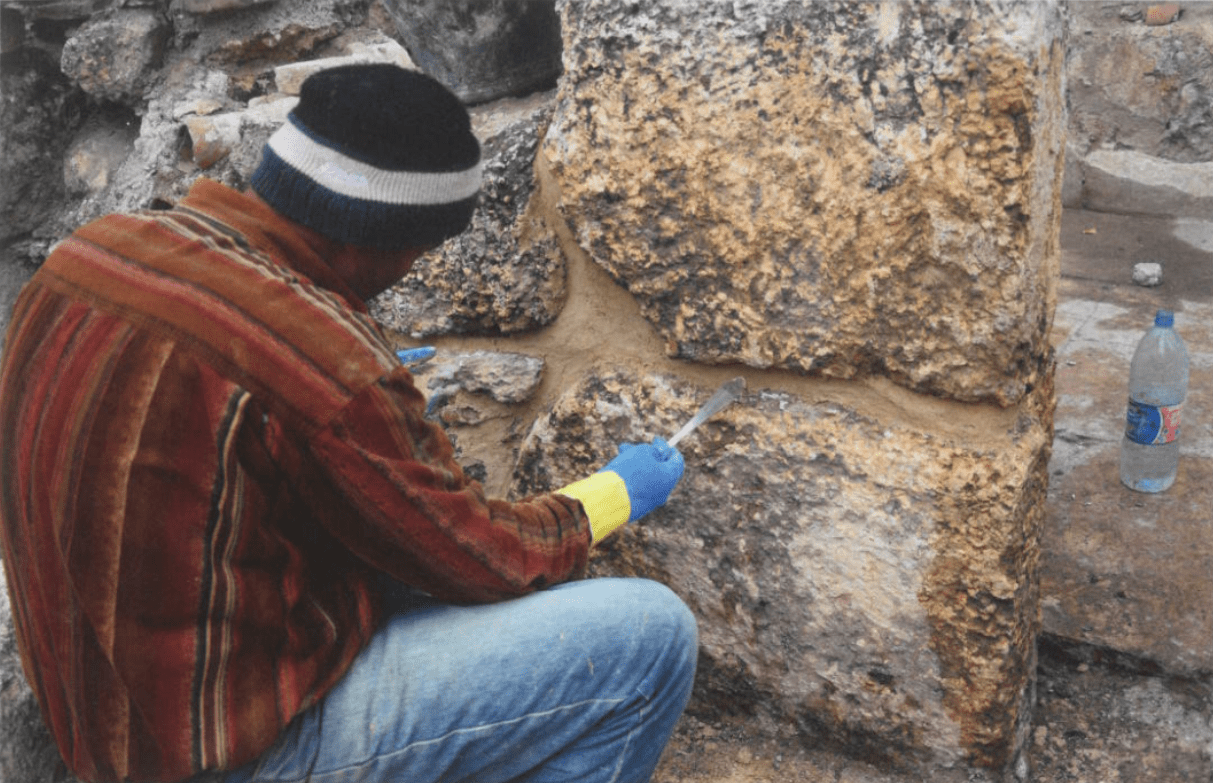

Conservation of a Medieval Quarter in Baalbek (Lebanon)

Baalbek is a UNESCO World Cultural Heritage site famous around the globe for its Roman temples. In the Middle Ages, Baalbek played an important part in the territorial conflicts between Crusaders and Arab rulers, growing to become a rich settlement near a fortress. The area of the town excavated in the 1970s dates back to this period. Thanks to a training project conservation work was conducted in the quarter and the area was made accessible for visitors.

von Dr. Dr. h.c. Margarete van Ess

Baalbek in Lebanon is the site of some of the most impressive ancient ruins in the world. In addition to the famous Roman temples, archaeological remains from the eighth millennium BC onwards have been preserved. So Baalbek’s history, still tangible for visitors, stretches back almost 10,000 years.

The further-training project being carried out on an excavated part of the town dating from the 12th to 16th centuries aims to preserve and present this diverse history. Right by what will be the new entrance to the ruins stand two small mosques, a caravanserai, public baths, town walls and several private houses. They bear witness to the town’s tumultuous history in the time of the conflicts between Crusaders and Ayyubid rulers, and to its sacking by the Mongols and subsequent reconstruction under the Mamluk dynasty.

Ancient and historical cultural sites are among Lebanon’s treasures. They attract tourists from all around the world and at the same time form a point of collective identity and economic resource for the local population. Preserving these cultural sites requires constant efforts by experienced craftsmen and specialist archaeologists and architects who can work not only in Baalbek but throughout the country. The training project, which is now completed, therefore offered quality training in conservation through constant upkeep, the conservation of structures at risk of erosion, the restoration and structural reinforcement of archaeological structures, and the art of presentation. It was directed both at Lebanese craftsmen and students and at Syrians who have fled to Lebanon.

The aim of the programme was to preserve and pass on – both within Lebanon and beyond – traditional and modern conservation techniques relating to the archaeological stone architecture typical of the entire region. That is why the programme fell under the project “Stunde Null: A Future for the Time after the Crisis” run by the German Archaeological Institute with funding from the Federal Foreign Office.

Over the course of three years, more than 70 people have participated in the project. In addition to providing training for young workers, this has also created job opportunities particularly for experienced older craftsmen who have been working in Baalbek to protect the ruins for decades and have now had the chance to pass on their knowledge about traditional techniques and measures which work well under the local conditions.

Students Safeguard Cultural Heritage

The project was an element of the practical training phases for student archaeologists at the Lebanese University, which assumed responsibility for training the local students in particular, along with many sub sidiary institutions in the country. It also benefitted from the cooperation with the Tripoli School of Architecture, which organises postgraduate courses in the conservation of Lebanon’s architectural heritage and seconded young architects to Baalbek to complete practical modules on the further-training project. The programme was thus closely integrated with training courses already on offer in Lebanon which are aimed both at young Lebanese nationals and at young Syrians who have found a new home in the country.

The scientific expertise relating to the archaeological and historical data and some aspects of the curricula came from the Orient Department of the German Archaeological Institute, which has been documenting and analysing the many different archaeological remains in Baalbek for over 20 years, as well as publishing the findings. This further-training project was thus exploring new ways to communicate the scientific findings to the local population and also to the Lebanese tourist industry.

Title image: Before conservation, missing sections have to be examined in detail and the original mortars determined|© DAI, Julia Nádor.

Quelle: Worlds of Culture – Foreign Policy for Cultural Heritage

Documenting the Drum Culture of Chiweshe and the Sungura and Mbira Guitar Styles (Zimbabwe)

The drum culture of Chiweshe and the Sungura and Mbira guitar styles are unique parts of Zimbabwe’s rich cultural heritage which are severely endangered as there are no musicians capable of capturing these skills and techniques to make them available for future generations. This project trained a group of musicians from the Music Crossroads Academy in Harare to document all three traditions on video and make transcriptions of the different styles.

Conservation of the Murals in Narathihapatae Hpaya Temple (Myanmar)

An earthquake hit the temple city of Bagan, one of the world’s most important historical cultural sites, in 2016. Almost 400 of the around 3000 sacred architectural works were damaged, some of them seriously. The extremely heavy spires of many temples fell to the ground, while centuriesold masonry became loose, cracking precious murals and stucco decorations.

Conservation in the Temple City of Bagan: From Conception to Realisation (Myanmar)

On 24 August 2016, an earthquake measuring 6.8 on the Richter scale hit the temple city of Bagan, one of the world’s most important historical cultural sites. Almost 400 of the around 3000 sacred architectural works were damaged, some of them seriously. The extremely heavy spires of many temples fell to the ground, while centuriesold masonry became loose, cracking precious murals and stucco decorations. Germany was one of the countries which responded to the urgent appeal for international help, sending three experts with many years of experience in cultural preservation in South-East Asia to Bagan to discuss suitable conservation and restoration measures with local officials.

Lahore Fort Picture Wall Prototype Project (Pakistan)

The Picture Wall at Lahore Fort, with all its extensive embellishments with tile mosaic and fresco panels, brick imitation and filigree work, represents the exceptional craftsmanship of the Mughal period. In 1981, Lahore Fort was therefore inscribed as a UNESCO World Heritage Site. The tile mosaics and frescoes have been severely damaged by disruptions to the original water drainage system and by exposure of the exterior facade to extreme weather conditions.

Stewards of Cultural Heritage wins an European Heritage Award/ Europa Nostra Award 2019

The Hague, 21 May 2019 – The project “Stewards of Cultural Heritage” was announced by the European Commission and Europa Nostra as one of the winners of the European Heritage Awards / Europa Nostra Awards 2019. The awards are Europe’s most prestigious honour in the field, funded by the Creative Europe programme.

Documentation of the Cultural Heritage of the Aché (Paraguay)

by Judith Brauner Amarilla (German Embassy in Asunción)

The Aché are an indigenous people living in Paraguay. Their cultural heritage consists of stories and traditions passed on orally which today are only known to a few tribal elders. The filming of documentaries and the creation of a virtual museum made it possible to record them and make them available to the Aché themselves, as well as to schools and the general public.

There are around 120,000 indigenous people living in Paraguay, who belong to 19 tribes. The indigenous population is divided into five different language groups, including the Guaraní language, which is Paraguay’s second official language. The Aché are a minority among the indigenous population. They currently number just under 1900 and live in seven groups. The people’s recent history is dramatic: until the 1970s, the Aché were hunted and sold as slaves. There was a slave market in southern Paraguay as recently as 1967.

In 1972, the German ethnologist Mark Münzel wrote about the genocide of the Aché in a publication, drawing international attention to this tragedy. The persecution of the Aché was finally stopped following international pressure. By that point, however, the people had already been torn apart and was scattered across different continents. The Aché were on the verge of extinction. Many elders were kidnapped and did not return to their groups until many years later. Because the Aché were no longer living together, it was not possible to pass on important parts of their culture to following generations in the oral tradition.

The Aché are aware of this situation and are seeking ways to preserve their culture. This is why the memories of the tribal elders were documented in three films as well as in a virtual museum. It has thus been made possible for the old stories and traditions, as well as the people’s recent history, to be preserved for coming generations and to make all of this accessible to them.

The team of the NGO Madre Tierra spent several weeks with the Aché group in Ypetimi filming the stories of the elders with a camera crew. They spoke about their lives in the forest, their traditions and customs, about the hunting down of adults and children and their later lives in exile far away from their tribe.

The oral nature of Aché culture has some unique features which are reflected in the documentaries. One typical feature is the continual repetition of single sentences, often in singing tones. The Aché speak very emotionally about their memories of life in the forest and the later persecution. Above all, the documentaries show this face of another culture. Traditional handicrafts are presented while the elders are telling their stories. Together with the elders, other tribe members made panniers, vessels and other everyday objects for the museum. The NGO Madre Tierra has been focusing on work with indigenous peoples since 2003.

With financial support from the German Embassy, a computer room was set up in the school in Ypetimi in 2016. This enabled indigenous people to use technology to preserve their own culture. The idea of cooperation within the framework of cultural preservation came from this small-scale measure. The virtual museum illustrating the Aché’s way of life is to be further developed and completed in future by members of the community.

Title image: Chevugi, 63, drawing his bow. The children and young people became interested in the elders’ handicrafts and traditions as a result of the filming | © Archivo de la Asociación Madre Tierra/ Patricia Ayala.

Funding:

Source:

Worlds of Culture. Foreign Policy for Cultural Heritage. 2018

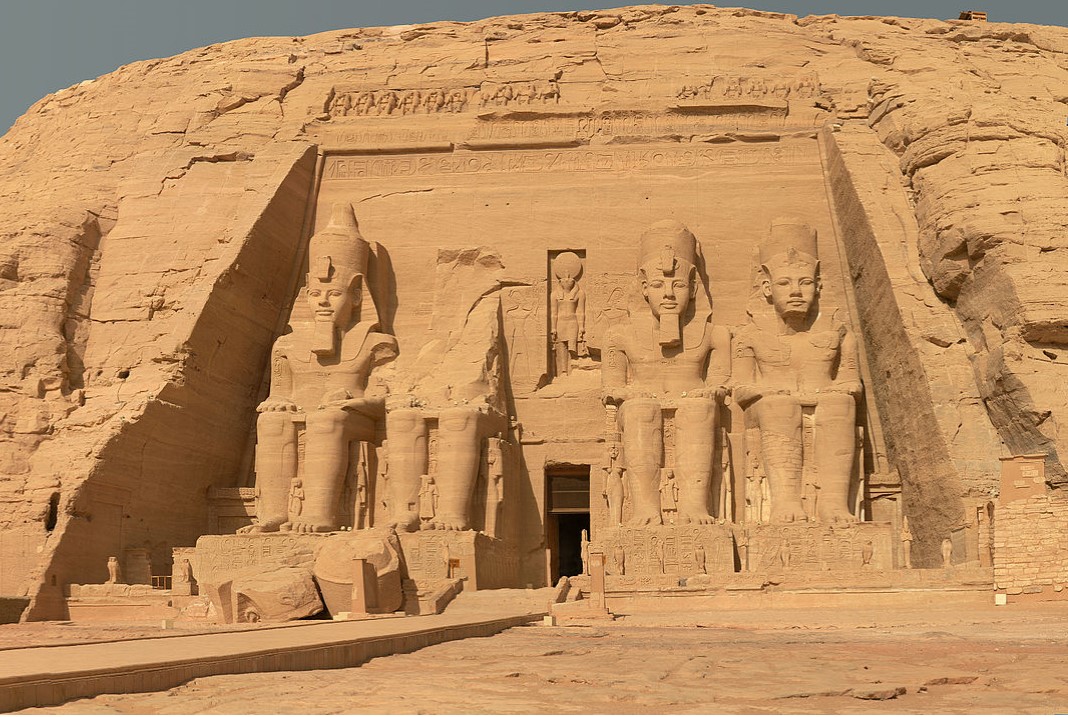

The Legacy of Abu Simbel and the Birth of an Idea

Ten days until the UNESCO Committee meets again to decide on the new World Heritage list. Let’s take a look back and revisit the point in time, when the idea of World Heritage was born. What does the Egyptian temples of Abu Simbel have to do with it?

Entangled History – European Year of Cultural Heritage

As part of the European Year of Cultural Heritage 2018 – Sharing Heritage, the German Archaeological Institute hosts several events including lectures and exhibitions.

Since its foundation on April 21, 1829 in Rome, the German Archaeological Institute (DAI) sees itself as a European research institution. The founding members from different European nations had set themselves the goal of researching and preserving the cultural heritage of Europe. The institute, which now operates with 19 locations and over 250 projects worldwide, has maintained this claim to this day. Of course, cultural heritage does not stop at the borders of Europe, but rather focuses on the cultural heritage of humanity worldwide – with all its links and mutual influence with and on Europe: Entangled History!

In the European Year of Cultural Heritage, the German Archaeological Institute created a platform for participation and exchange at its Europe-wide locations. The exhibitions, lectures, discussions and conferences refer to the theme “Europe: exchange and movement” – one of five main themes of the year.

The following exhibitions in the framework of “Entangled History”can be visited in Turkey and Germany this summer:

Pergamon Resurrected! – New Exhibition on the 3D Reconstructions of an antique city (Turkey)

Photo Exhibition in Bergama – Neither in Heaven nor on Earth (Turkey)

Find out more about events of Sharing Heritage – European Heritage Year 2018.

World Heritage – Facts and Figures

The World Heritage Committee meets again in a few weeks in Bahrain to select the sites that will be listed in the UNESCO World Heritag List. Time for some Facts and figures before the big day arrives.

UNESCO adopted the convention concerning the protection of the World cultural and natural heritage on 16 November 1972. It entered into force in 1975, and the first inscriptions on the World Heritage list followed in 1978. The convention defines cultural and natural heritage in a way that views in its entirety, in its overall context; and it states that it is incumbent on the international community as a whole to take part in protecting world heritage and transmitting it to future generations. In 1982 the old city of Jerusalem, “in view of the special political situation”, was the first cultural heritage site to be entered on a list of World heritage in danger. To date, the convention has been ratified by 190 states. Each state that is party to the convention recognizes the duty of ensuring protection of World Heritage sites within their frontiers and of conserving them for future generations.

On the adoption of the global Strategy in 1994, the concept of cultural heritage was enlarged, with “cultural landscape” being added as a subcategory of “cultural site”. The UNESCO attaches priority to nominations from countries that don’t yet figure on the World Heritage list. This is because more than half of all world heritage sites formerly lay in Europe and North America. The definition of cultural heritage in Article 1 of the convention reflected the western world’s own definition of itself with reference to cultural heritage in the 1960s. In 1994 the Nara document on Authenticity, adopted in Nara, Japan, opened the way for the recognition of non-western concepts and techniques of conservation. The further development of the world heritage idea is also reflected in the membership of the World heritage committee. On this body, members from the southern hemisphere are gradually replacing and outnumbering members from the north.

2018: 1.000 sites under UNESCO protection

Over 1.000 cultural and natural heritage sites representing all the continents are registered on the UNESCO World heritage list. Of the 193 States parties to the UNESCO convention on the protection of cultural and natural heritage, 167 have properties on the World heritage list. The list of World Heritage in danger currently numbers 54 World Heritage sites, including the Old City of Sana’a in Yemen, the ancient city of Palmyra, Assur in Irak, the early Christian ruins of Abu Mena in Egypt and Everglades National Park in America. The UNESCO World Heritage committee checks every year whether the sites are still in danger. The World Heritage committee meets once a year to decide, among other things, on inscriptions on the World Heritage list. This year the 42nd session of the World Heritage Committee will take place between June 24 and July 4 in Bahrain. Proposals for inscription may only be submitted by member states, which, by doing so, accept responsibility for preservation of the site.

Source: Archaeology Worldwide 2015

Image: Temple of Angkor Wat, Cambodia | pxhere.

Read more:

The Path to World Heritage

In a few weeks, between June 24 and July 4 2018, the World Heritage List will be reassessed in Bahrain during the 42. Session of the World Heritage Committee. Every year the Committee meets to select the sites to be listed on the UNESCO Word Heritage List. But what does it take to get on the Cultural Heritage List of the UNESCO?

UNESCO requires the following commitment from states that have world heritage sites on their territory: “By signing the convention the States parties undertake to protect the world heritage sites lying within their borders and to preserve them for future generations.” There are ten criteria, one of which must be met, in order for a site, monument or feature to be designated world heritage. A cultural asset is deemed to be of “outstanding universal value” if, for example, it is a “masterpiece of human creative genius”, is representative of a type of art, building or landscape or an architectural or technological ensemble which reflects an important phase in human history, or if it bears witness to a cultural tradition or to a civilization that has disappeared. A site is considered to be natural heritage if it contains “superlative natural phenomena or areas of exceptional natural beauty and aesthetic importance”, if it illustrates a major phase in the earth’s history, represents significant ecological and biological processes, or contains important natural habitats for in-situ conservation of biological diversity.

From Nomination to Inscription

The phase from the nomination to the inscription of newly proposed properties lasts at least 18 months – from February of a given year until the World Heritage Committee session in June/ July of the following year when a decision will be taken. The process begins with the UNESCO World Heritage centre inviting member states to submit a tentative list of properties situated within their borders which they may consider proposing for nomination. Nominations are then submitted before the 1st February deadline for evaluation and decision-making the following year.

Submissions are assessed on behalf of the UNESCO World Heritage Committee by the international council on Monuments and Sites (ICOMOS) and the international Union for the conservation of nature (IUCN). On the basis of this expert evaluation the World Heritage committee then makes its final decision on whether or not nominated sites are to be inscribed on the world heritage list.

Obligations

But what does it actually mean when a monument, area or landscape changes its status, is no longer simply a site in a particular country, no longer “belongs” solely to that country, but suddenly becomes the “property” of all mankind? With the altered status comes a change in the state’s obligations, which now undertakes to protect and to preserve that portion of world heritage that is situated on its territory. Article 4 of the UNESCO World Heritage convention declares that each State party recognizes that “the duty of ensuring the identification, protection, conservation, presentation and transmission to future generations of the cultural and natural heritage referred to in Articles 1 and 2 and situated on its territory, belongs primarily to that State. It will do all it can to this end, to the utmost of its own resources and, where appropriate, with any international assistance and cooperation, in particular, financial, artistic, scientific and technical, which it may be able to obtain”.

This is followed by a list of political, legal, financial, and personnel and infrastructure related measures that are considered appropriate for the preservation of cultural heritage for later generations. The main requirements in this catalogue are “to develop scientific and technical studies and research, […] to work out such operating methods as will make the State capable of counteracting the dangers that threaten its cultural or natural heritage [and] to foster the establishment or development of national or regional centres for training in the protection, conservation and presentation of cultural and natural heritage”.

In-Depth Analysis

Archaeological research works at the very core of these definitions of world heritage and the catalogue of requirements for its preservation. Using the multi- and interdisciplinary methods described above, it investigates decisive changes in the course of human history: the introduction of agriculture and herding, the emergence of urban centres and complex systems of society, and the formation of symbolic order, which in many cases are the foundations of what still constitutes an important part of our implicit knowledge and thinking. Traces of human activity can be found in spectacular objects like colossal statues or in tiny fragments of papyrus.

Architecture presents us with evidence of the past, but the evidence is not always immediately apparent, sometimes only revealing itself in reconstructions. Layer by layer, archaeologists unearth material remains in excavations, and use pile core analyses to create vegetation and climate archives; bones, plant remains and wood yield as much information about people’s way of life and mode of subsistence as ceramic and metal artefacts do. Texts, chiselled in stone, written on papyrus or imprinted in clay, allow all facets of past societies – whether state treaties, epic poetry or everyday accounting – to emerge into view. Research is concerned with understanding the overall context.

Site Management and Sustainable Tourism

To ensure the excavated and vulnerable archaeological remains are preserved for future generations and to make both research and sustainable tourism viable at excavation sites, what is required is integral site management that encompasses an archaeological site or a cultural landscape in its entirety. How exactly should the historical remains be prepared for and displayed to tourists? And above all, how can the remains be protected in a way that is sustainable and complies with conservation practice? Whatever the measures taken, research and scientific documentation are essential requirements.

Several German sites funded by the Cultural Preservation Programme of the Federal Foreign Office belong to the World Heritage List. The German Archaeological Institute works towards the preservation and sustainable maintenance of cultural heritage in its host and partner countries in Europe and worldwide. In doing so, it engages in active cultural policy and moreover is often able, through its archaeological work, to contribute towards regional economic development in those countries.

Source: Archaeology Worldwide (Pdf)

Image: Lion gate at the World Heritage Hattusha in Turkey. flickr.com