Ten days until the UNESCO Committee meets again to decide on the new World Heritage list. Let’s take a look back and revisit the point in time, when the idea of World Heritage was born. What does the Egyptian temples of Abu Simbel have to do with it?

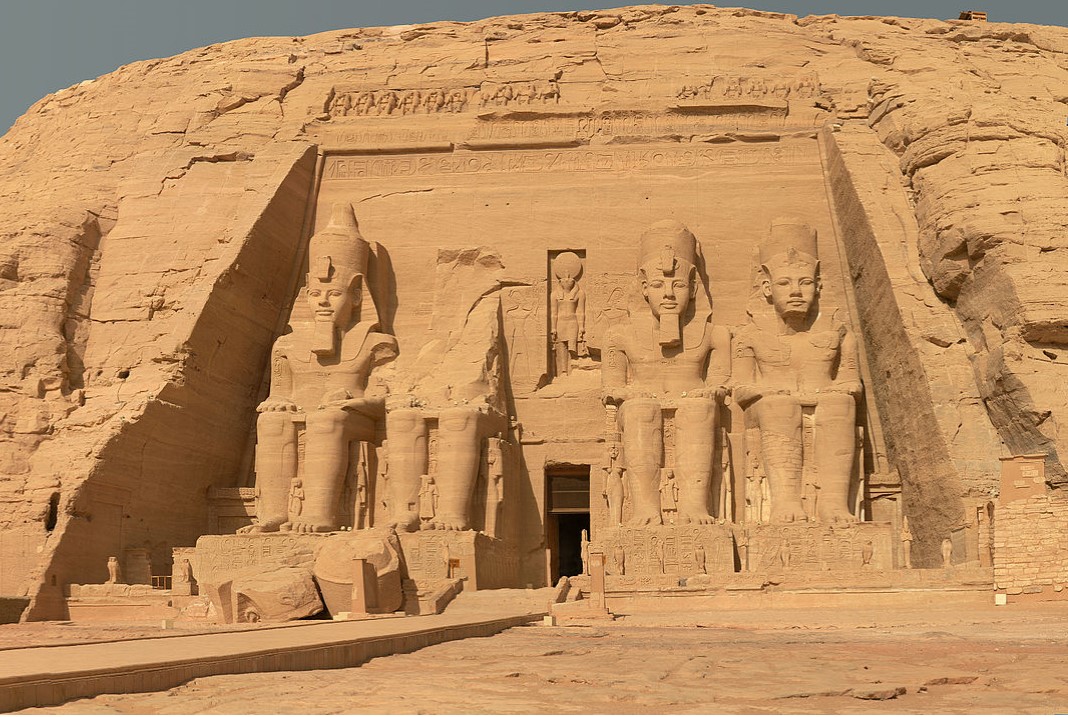

It was a last-minute rescue operation. The UNESCO appealed to the world for help. The monumental temple at Abu Simbel, more than 3,000 years old, was going to be submerged by the newly created Aswan dam and lost for ever. The temple of pharaoh Ramses II had been cut into the rock on the west bank of the Nile, and extended nearly 60 metres deep into the sandstone. Gamal Abdel Nasser, Egyptian president since 1952, had decided to dam the Nile south of Aswan to create a vast drinking water reservoir. In 1959, Egypt asked UNESCO for assistance, and one year later the UNESCO director-general, Vittorino Veronese, uttered the words that ever since have formed the essence of the definition of what World Heritage is: “these monuments […] do not belong solely to the countries who hold them in trust. The whole world has the right to see them endure.” In a passionately worded appeal, Veronese called on the governments of the world, as well as institutions and foundations and all people of good will, to join in the task of saving the ancient Egyptian complex.

Moving mountains – The relocation of Abu Simble

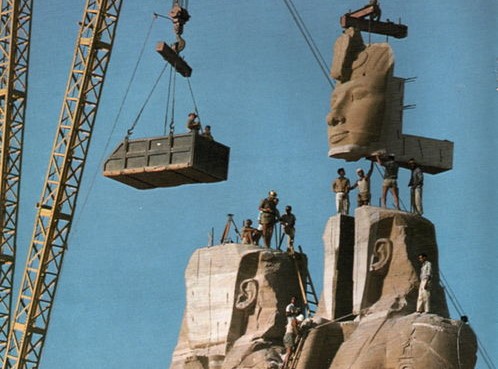

The two temples at Abu Simbel were then moved to a new site in a multinational collaborative project involving 50 countries. The project lasted from November 1963 to September 1968 and by the end the costs had amounted to about 80 million dollars. UNESCO’s salvage plan envisaged moving the temple of Ramses II to a safe location. An international consortium under the direction of the German construction company Hochtief was charged with the technical realization of the project. In the end a Swedish scheme was selected, which proposed that the temples should be cut into blocks, dismantled and then reassembled piece by piece – 64 metres higher up and 180 metres further inland. In this way 1,036 blocks weighing up to 30 tons were moved. Italian specialists with experience in marble working were engaged for the dissection of the Ramses statues. 2,000 workers, craftsmen, engineers, archaeologists and other experts from all round the world worked together to rescue what was viewed, for the first time, as the shared heritage of humankind.

The Aftermath – Lessons learnt

The lesson had been learnt, from the experience of the Second World War, that “a peace based exclusively upon the political and economic arrangements of governments would not be a peace which could secure the unanimous, lasting and sincere support of the people of the world, and that the peace must therefore be founded, if it is not to fail, upon the intellectual and moral solidarity of mankind” – as the UNESCO constitution, signed on 16 November 1945, declares. The newly founded organization had the mission of contributing to peace and security by promoting international collaboration through education, science, culture and communication. The Federal republic of Germany joined the organization on 11 July 1951, the German democratic republic in 1972.

On 16 November 1972, UNESCO adopted the convention concerning the protection of the World Cultural and Natural Heritage. The central idea of the World Heritage convention is that “parts of the cultural or natural heritage are of outstanding interest and therefore need to be preserved as part of the world heritage of mankind as a whole”. It is the most significant instrument created by the international community for the purpose of protecting its cultural and natural heritage. To date, the convention has been ratified by 193 states. The UNESCO World Heritage list was established in 1978, and the Abu Simbel temples were inscribed as the very first World Cultural Heritage site in 1979. As of 2018, the list includes over 1,000 cultural and natural monuments in 167 states that are party to the convention.

Global common goods

The World Heritage idea is part of the concept of “global common goods” that was introduced in the 1960s by the United Nations development programme. These common goods include a clean and intact environment, a stable climate, stable financial markets, peace, security, health – and cultural heritage. The protection of cultural and natural treasures as “World Heritage” had the aim of creating a global knowledge reservoir of all cultural accomplishments and all life on earth and making this knowledge available to everybody as a resource.

Source: Archäologie Weltweit 1-2015 Sonderausgabe en

Image: Temples of Abu Simbel|Wiki Commons.

Read more: