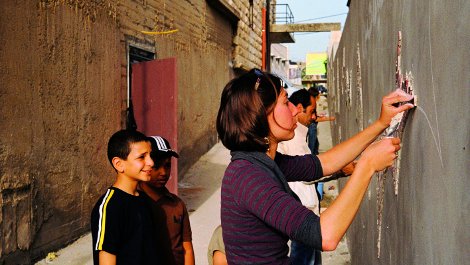

As the stars ascend over the West Bank, the neon light goes down in the open-air cinema’s projection house. The projector flickers into life and the rotating beam hits the screen. The moment everyone has been waiting for has come: 23 long years since the last screening, films are showing once more in Jenin. Cinema Jenin’s renaissance was made possible by funds from the Federal Foreign Office and numerous other foreign sponsors. On the ground Palestinian and international volunteers, supported by local experts and business people, worked together for nearly two years on the reconstruction of the only cinema in the north of the West Bank.

It was not always easy to get this kind of project off the ground in Jenin. There are still many people here who reject any form of “normalization” in the form of cultural and partner projects. The mistrust of the Israeli authorities sits too deep in the local population.

However the number of those prepared to make peace on a one-to-one level is growing. This is also thanks to Cinema Jenin and the team of international and Palestinian workers.

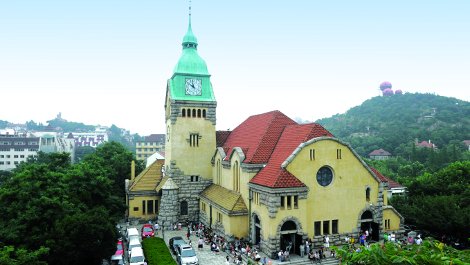

The history of the cinema is closely connected with the history of the Middle East conflict. The cinema had to close in 1987 during the first Intifada. In the years that followed, the building, with its broadly international style, fell more and more into disrepair.

In 2008 the German film-maker Marcus Vetter came to Jenin to tell the story of Palestinian Ismael Khatib. Khatib’s son was shot by the Israeli army in the former refugee camp of Jenin. His father decided to offer up his organs for donation – including to Israeli children. The case attracted a great deal of international attention. In April 2010 Vetter’s documentary “The Heart of Jenin” won the German Film Award 2010.

During filming Khatib drew the director’s attention to the empty building. An idea was soon hatched to make the town’s cinema accessible to the public once again. When the Federal Foreign Office heard about the project, it provided start-up funds, which were later considerably increased. Soon supporters for the project appeared from all over the world.

A cooperative project was born which is based on dialogue and the idea that participants organize themselves. The project involves local people at grassroots level and facilitates follow-on projects. As such it could serve as a model for sustainable development in the Middle East.

In around two years amazing things have been achieved. The stage has been restored and a total of 400 seats refurbished in the stalls and upstairs gallery. New sound and lighting equipment makes for a professional sound. A German cinema chain donated projectors, and soon even 3-D films will be shown. A summer garden with projection house sprung up from nothing.

Palestinian Prime Minister Fayyad came to the opening on 5 August 2010. Young Palestinians and international guests crowded together in front of the red carpet. At the last minute the “Cinema Jenin” sign was fixed above the entrance. The town was in a state of frenzied excitement.

On the opening evening, as one looked at the faces of the people sitting together in the open-air cinema watching “The Heart of Jenin”, one could not but believe in the power of cinema to bring peace. The cinema theatre is a magical space of dreams and illusions – and there is a grateful audience in Jenin ready to enjoy it.

Author: Ruben Donsbach, Journalist, Berlin

Promoted by: Cultural Preservation Programme of The Federal Foreign Office

Source: Worlds of Culture, Ed. Federal Foreign Office