Thanks to the digitisation of northern Thai manuscripts as part of the Cultural Preservation Programme of the Federal Foreign Office, valuable historical documents have been preserved and made available to the public via the internet.

The cultural and literary traditions of northern Thailand have made an essential contribution to the development of related cultures throughout the region. However, northern Thailand’s rich manuscript collections have remained severely under-researched due to a lack of accessibility. The database of northern Thai literature is therefore an important milestone in efforts to preserve Thailand’s cultural heritage. The texts, which span more than 500 years, address cultural and local traditions, astrology, mythology, legal interpretations, social relations and everyday life; they are not only part of the country’s cultural heritage, but also strengthen the Thai people’s cultural identity.

The Federal Foreign Office already between 1987 and 1992 supported the creation of a microfilm record of northern Thai manuscripts. This microfilm collection was later digitised with funds from the Cultural Preservation Programme. Since March 2016 it is publicly available on the internet, free of charge. In 2017, selected manuscripts from 22 temples in Lamphun, Lampang, Phayao and Chiang Rai were directly digitised, thereby completing the online collection.

The manuscripts are being digitised in northern Thailand by a photographer and a handwriting expert. Their work is supported by local volunteers and supervised by the project leader and the technical coordinator. All work is performed directly at each temple, in coordination with the local abbot. Once the digitisation is completed, each manuscript is carefully wrapped in its piece of cloth and returned to where it was originally stored.

Just prior to being photographed, each manuscript is cleaned and examined. Some leaves are wiped with high-grade alcohol to make them more easily readable. The project staff and local monks involved in the project are offered training to show them how to properly clean and arrange the individual palm leaves.

A digital single-lens reflex camera is highly portable and takes high-quality photos that can be archived and viewed on the internet. The photos are later added to the Digital Library of Northern Thai Manuscripts, along with the respective inventory data in English and Thai.

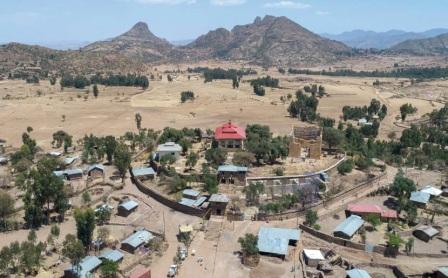

To round out the manuscript website, photos are uploaded of temples, libraries, manuscript boxes, scribes and the direct digitisation process.

Image: A manuscript at Wat Pa Sak Noi Temple | © 2015 David Wharton, Digital Library of Northern Thai Manuscripts

Promoted by: Cultural Preservation Programme of The Federal Foreign Office

Source: Ed. Federal Foreign Office