The largest of the Egyptian pharaohs’ temples, the sun temple of Heliopolis, lies at the heart of pulsating everyday life in the megacity Cairo. Its survival is under threat from informal construction, rising groundwater levels and emerging rubbish dumps. The open-air museum devoted to the archaeological site Heliopolis with its temples, houses and graves, the result of an initiative by the Egyptian Ministry of Antiquities, is something of an island in the middle of Matariya district. With funding from the Cultural Preservation Programme of the Federal Foreign Office, a protective roof is to be erected over the museum so that the most recently found, environmentally sensitive treasures of Ancient Egyptian art can be presented to the local population and visitors.

by Aiman Ashmawy (Head of the Archaeological Sector, Ministry of Antiquities of the A. R. E) and Dietrich Raue (Custodian of the Egyptian Museum – Georg Steindorff – of the University of Leipzig)

The cult of the sun was of central importance to religion in Ancient Egypt. For many centuries, Heliopolis, the cult’s most important centre, has stood in an area which is today part of the city of Cairo. The place where Ancient Egyptians believed the world to have been created lies in Matariya district. World-famous monuments from Matariya, such as obelisks in Rome, Florence, London and New York, testify to the original dimensions of the sun temple.

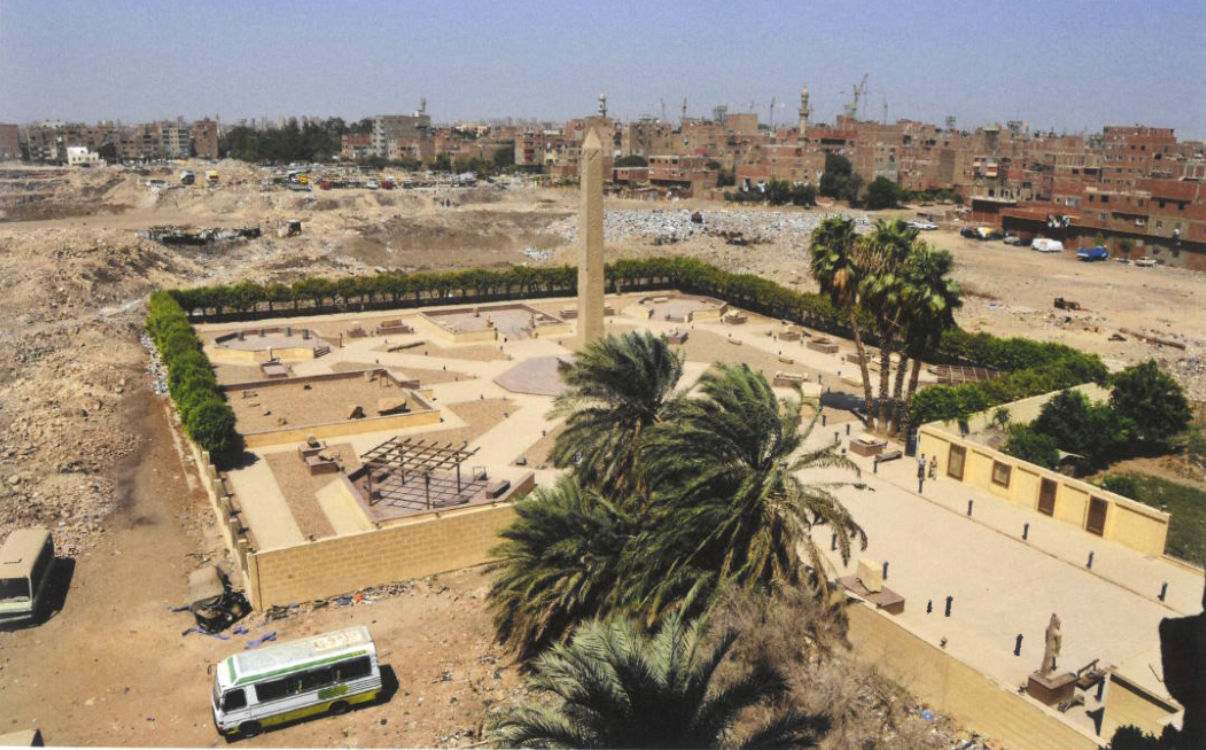

In the centuries following the pharaonic era, the area around the sun temple of Heliopolis was the site of major construction work in Cairo. The 11th-century city walls, for example, were built to no small extent from blocks of stone from the temple of Heliopolis, which stood just nine kilometres to the north. Of the huge ancient sacred area, roughly 1100 × 950 metres, several hectares have in the meantime been built over as Cairo has developed into a modern megalopolis. Matariya is one of the low-income districts which was particularly hard hit by economic problems in the wake of the revolution in spring 2011. Illegal rubbish dumps, some of them up to 14 metres in height, have mushroomed in many non-built-up areas as a result of the lack of legal controls since 2011.

The open-air museum devoted to the Heliopolis archaeological site, which has been used for some decades now to exhibit large temple blocks, pillars, sarcophaguses and statues, lies in the midst of this district. The museum is designed around one of the few large-scale obelisks in Egypt that has constantly remained standing. This monolith to King Sesostris I, hewn from pink granite and 20.8 metres tall, has stood testament to the scale of Heliopolis since around 1950 BC. Shortly before the revolution in 2011, the Supreme Council of Antiquities had launched a programme to modernise the exhibition. Following an interruption of several years, the museum opened to the public in February 2018. A host of objects on display demonstrate the important place this religious centre occupied in Ancient Egyptian culture.

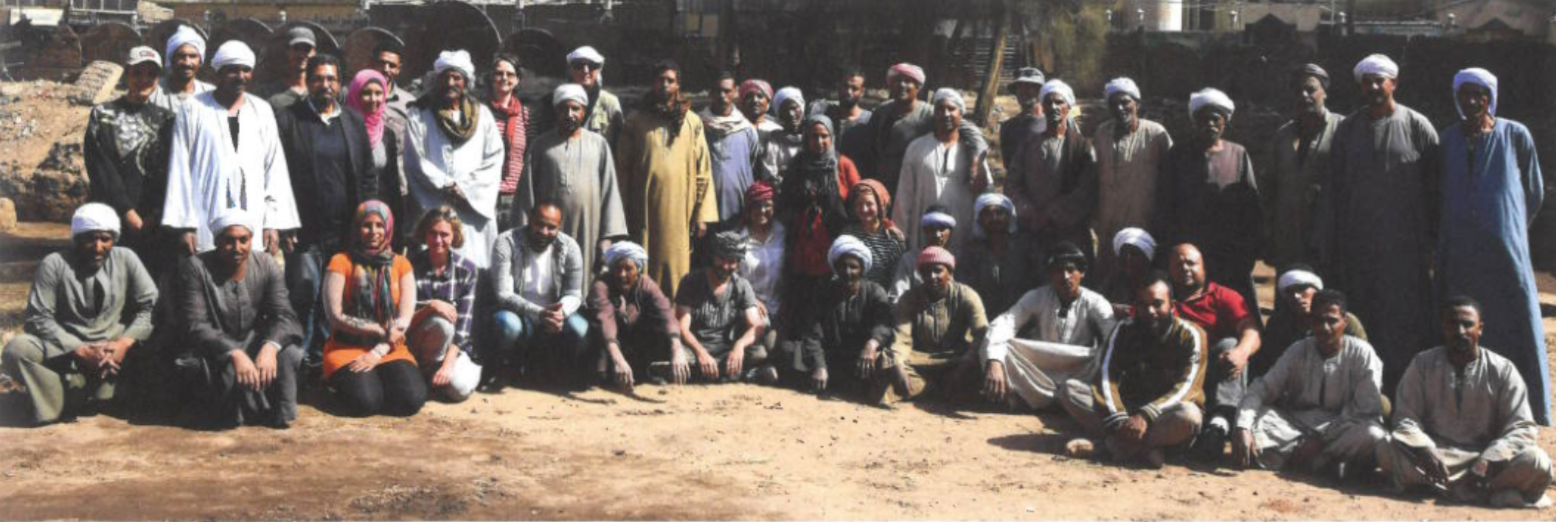

Since 2012, a joint Egyptian-German team has been working, with help from the local community, to systematically record and excavate the temple site, at jeopardy as a result of the latest developments in the area. An international team of researchers from the Egyptian Ministry of Antiquities, the University of Leipzig and the University of Applied Sciences in Mainz have carried out a number of emergency excavations with support from the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (German Research Foundation) to examine the cultural heritage at this unique site.

The monuments, which date from the third to first millennium BC and bear witness to the site’s constant importance for the pharaohs over 2400 years, are rooted up to three metres below the steadily rising groundwater level. The most important finds in recent years include a number of basalt reliefs and inscriptions dating from the time of King Nectanebo I (380–363 BC) which are outstanding examples of the artistry of their time. Because the material is very sensitive to strong sunlight, however, it cannot be on unrestricted display in an open-air museum.

Finely worked and well-preserved quartzite reliefs of Ramses II (1279–1213 BC) were found in the same temple. In order to preserve these highlights of Ancient Egyptian art as proof of the site’s cultural significance for the local population, a new section of building with a suitable protective roof is being planned. The reopening, with evidence-based and informative texts, is scheduled for October 2018.

The exhibition is designed both to show local people the depth and diversity of their culture and to attract international visitors.

Title Image: Ramses II making a sacrifice to the sun god: quartzite doorway from the temple of Heliopolis (excavations in spring 2018) | © Dietrich Raue.

Promoted by: Cultural Preservation Programme of The Federal Foreign Office

Source: Worlds of Culture – Foreign Policy for Cultural Heritage