Göbekli Tepe is one of the most impressive Stone Age sites in the world. On June 24 the World Heritage Committee will decide if the site is going to be included in the World Heritage List. Find out more about recent developements at Göbekli Tepe!

Month: June 2018

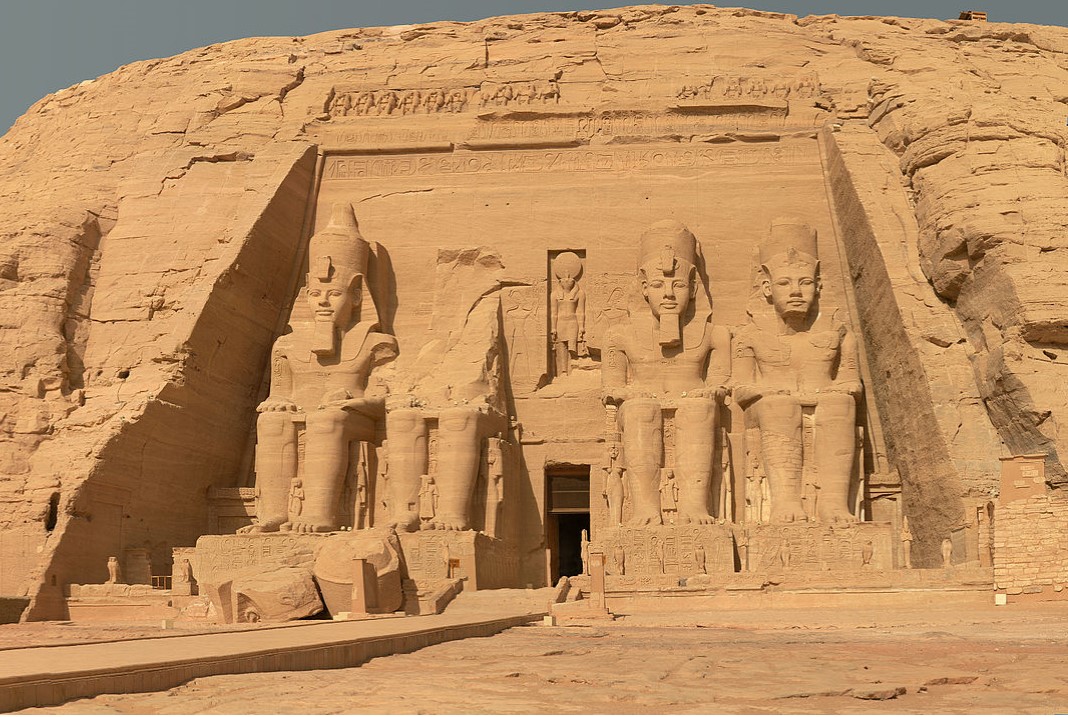

The Legacy of Abu Simbel and the Birth of an Idea

Ten days until the UNESCO Committee meets again to decide on the new World Heritage list. Let’s take a look back and revisit the point in time, when the idea of World Heritage was born. What does the Egyptian temples of Abu Simbel have to do with it?

Entangled History – European Year of Cultural Heritage

As part of the European Year of Cultural Heritage 2018 – Sharing Heritage, the German Archaeological Institute hosts several events including lectures and exhibitions.

Since its foundation on April 21, 1829 in Rome, the German Archaeological Institute (DAI) sees itself as a European research institution. The founding members from different European nations had set themselves the goal of researching and preserving the cultural heritage of Europe. The institute, which now operates with 19 locations and over 250 projects worldwide, has maintained this claim to this day. Of course, cultural heritage does not stop at the borders of Europe, but rather focuses on the cultural heritage of humanity worldwide – with all its links and mutual influence with and on Europe: Entangled History!

In the European Year of Cultural Heritage, the German Archaeological Institute created a platform for participation and exchange at its Europe-wide locations. The exhibitions, lectures, discussions and conferences refer to the theme “Europe: exchange and movement” – one of five main themes of the year.

The following exhibitions in the framework of “Entangled History”can be visited in Turkey and Germany this summer:

Pergamon Resurrected! – New Exhibition on the 3D Reconstructions of an antique city (Turkey)

Photo Exhibition in Bergama – Neither in Heaven nor on Earth (Turkey)

Find out more about events of Sharing Heritage – European Heritage Year 2018.

World Heritage – Facts and Figures

The World Heritage Committee meets again in a few weeks in Bahrain to select the sites that will be listed in the UNESCO World Heritag List. Time for some Facts and figures before the big day arrives.

UNESCO adopted the convention concerning the protection of the World cultural and natural heritage on 16 November 1972. It entered into force in 1975, and the first inscriptions on the World Heritage list followed in 1978. The convention defines cultural and natural heritage in a way that views in its entirety, in its overall context; and it states that it is incumbent on the international community as a whole to take part in protecting world heritage and transmitting it to future generations. In 1982 the old city of Jerusalem, “in view of the special political situation”, was the first cultural heritage site to be entered on a list of World heritage in danger. To date, the convention has been ratified by 190 states. Each state that is party to the convention recognizes the duty of ensuring protection of World Heritage sites within their frontiers and of conserving them for future generations.

On the adoption of the global Strategy in 1994, the concept of cultural heritage was enlarged, with “cultural landscape” being added as a subcategory of “cultural site”. The UNESCO attaches priority to nominations from countries that don’t yet figure on the World Heritage list. This is because more than half of all world heritage sites formerly lay in Europe and North America. The definition of cultural heritage in Article 1 of the convention reflected the western world’s own definition of itself with reference to cultural heritage in the 1960s. In 1994 the Nara document on Authenticity, adopted in Nara, Japan, opened the way for the recognition of non-western concepts and techniques of conservation. The further development of the world heritage idea is also reflected in the membership of the World heritage committee. On this body, members from the southern hemisphere are gradually replacing and outnumbering members from the north.

2018: 1.000 sites under UNESCO protection

Over 1.000 cultural and natural heritage sites representing all the continents are registered on the UNESCO World heritage list. Of the 193 States parties to the UNESCO convention on the protection of cultural and natural heritage, 167 have properties on the World heritage list. The list of World Heritage in danger currently numbers 54 World Heritage sites, including the Old City of Sana’a in Yemen, the ancient city of Palmyra, Assur in Irak, the early Christian ruins of Abu Mena in Egypt and Everglades National Park in America. The UNESCO World Heritage committee checks every year whether the sites are still in danger. The World Heritage committee meets once a year to decide, among other things, on inscriptions on the World Heritage list. This year the 42nd session of the World Heritage Committee will take place between June 24 and July 4 in Bahrain. Proposals for inscription may only be submitted by member states, which, by doing so, accept responsibility for preservation of the site.

Source: Archaeology Worldwide 2015

Image: Temple of Angkor Wat, Cambodia | pxhere.

Read more:

The Path to World Heritage

In a few weeks, between June 24 and July 4 2018, the World Heritage List will be reassessed in Bahrain during the 42. Session of the World Heritage Committee. Every year the Committee meets to select the sites to be listed on the UNESCO Word Heritage List. But what does it take to get on the Cultural Heritage List of the UNESCO?

UNESCO requires the following commitment from states that have world heritage sites on their territory: “By signing the convention the States parties undertake to protect the world heritage sites lying within their borders and to preserve them for future generations.” There are ten criteria, one of which must be met, in order for a site, monument or feature to be designated world heritage. A cultural asset is deemed to be of “outstanding universal value” if, for example, it is a “masterpiece of human creative genius”, is representative of a type of art, building or landscape or an architectural or technological ensemble which reflects an important phase in human history, or if it bears witness to a cultural tradition or to a civilization that has disappeared. A site is considered to be natural heritage if it contains “superlative natural phenomena or areas of exceptional natural beauty and aesthetic importance”, if it illustrates a major phase in the earth’s history, represents significant ecological and biological processes, or contains important natural habitats for in-situ conservation of biological diversity.

From Nomination to Inscription

The phase from the nomination to the inscription of newly proposed properties lasts at least 18 months – from February of a given year until the World Heritage Committee session in June/ July of the following year when a decision will be taken. The process begins with the UNESCO World Heritage centre inviting member states to submit a tentative list of properties situated within their borders which they may consider proposing for nomination. Nominations are then submitted before the 1st February deadline for evaluation and decision-making the following year.

Submissions are assessed on behalf of the UNESCO World Heritage Committee by the international council on Monuments and Sites (ICOMOS) and the international Union for the conservation of nature (IUCN). On the basis of this expert evaluation the World Heritage committee then makes its final decision on whether or not nominated sites are to be inscribed on the world heritage list.

Obligations

But what does it actually mean when a monument, area or landscape changes its status, is no longer simply a site in a particular country, no longer “belongs” solely to that country, but suddenly becomes the “property” of all mankind? With the altered status comes a change in the state’s obligations, which now undertakes to protect and to preserve that portion of world heritage that is situated on its territory. Article 4 of the UNESCO World Heritage convention declares that each State party recognizes that “the duty of ensuring the identification, protection, conservation, presentation and transmission to future generations of the cultural and natural heritage referred to in Articles 1 and 2 and situated on its territory, belongs primarily to that State. It will do all it can to this end, to the utmost of its own resources and, where appropriate, with any international assistance and cooperation, in particular, financial, artistic, scientific and technical, which it may be able to obtain”.

This is followed by a list of political, legal, financial, and personnel and infrastructure related measures that are considered appropriate for the preservation of cultural heritage for later generations. The main requirements in this catalogue are “to develop scientific and technical studies and research, […] to work out such operating methods as will make the State capable of counteracting the dangers that threaten its cultural or natural heritage [and] to foster the establishment or development of national or regional centres for training in the protection, conservation and presentation of cultural and natural heritage”.

In-Depth Analysis

Archaeological research works at the very core of these definitions of world heritage and the catalogue of requirements for its preservation. Using the multi- and interdisciplinary methods described above, it investigates decisive changes in the course of human history: the introduction of agriculture and herding, the emergence of urban centres and complex systems of society, and the formation of symbolic order, which in many cases are the foundations of what still constitutes an important part of our implicit knowledge and thinking. Traces of human activity can be found in spectacular objects like colossal statues or in tiny fragments of papyrus.

Architecture presents us with evidence of the past, but the evidence is not always immediately apparent, sometimes only revealing itself in reconstructions. Layer by layer, archaeologists unearth material remains in excavations, and use pile core analyses to create vegetation and climate archives; bones, plant remains and wood yield as much information about people’s way of life and mode of subsistence as ceramic and metal artefacts do. Texts, chiselled in stone, written on papyrus or imprinted in clay, allow all facets of past societies – whether state treaties, epic poetry or everyday accounting – to emerge into view. Research is concerned with understanding the overall context.

Site Management and Sustainable Tourism

To ensure the excavated and vulnerable archaeological remains are preserved for future generations and to make both research and sustainable tourism viable at excavation sites, what is required is integral site management that encompasses an archaeological site or a cultural landscape in its entirety. How exactly should the historical remains be prepared for and displayed to tourists? And above all, how can the remains be protected in a way that is sustainable and complies with conservation practice? Whatever the measures taken, research and scientific documentation are essential requirements.

Several German sites funded by the Cultural Preservation Programme of the Federal Foreign Office belong to the World Heritage List. The German Archaeological Institute works towards the preservation and sustainable maintenance of cultural heritage in its host and partner countries in Europe and worldwide. In doing so, it engages in active cultural policy and moreover is often able, through its archaeological work, to contribute towards regional economic development in those countries.

Source: Archaeology Worldwide (Pdf)

Image: Lion gate at the World Heritage Hattusha in Turkey. flickr.com